The destruction of Bickford’s

At some point in the late 1990s, when New York City finally sold it soul to the Disney Corporation and Disney began tearing down the store front facades along the uptown side of 42nd Street between 7th and 8th Avenues, they uncovered quite by accident one of the icons of the Beat movement.

In those days, I walked there pretty often, trying to get a last glimpse at what I considered “the real Times Square,” before Disney make it Disney World North, and uninhabitable for ordinary people to transverse.

The phony facades that had been slapped up over older facades like layers of paint in the old Lower East Side apartment I once lived in had been pealed away, exposing the previous generation of store front, long lost stores no one had any reason to remember – save one.

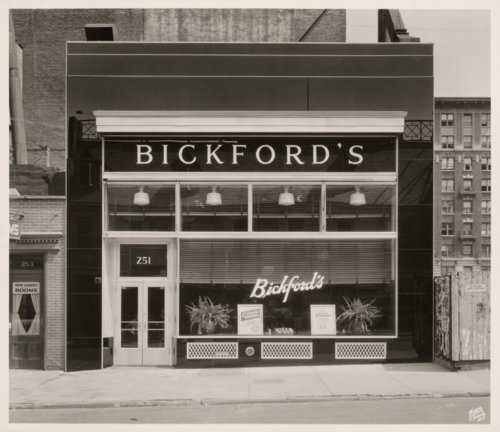

About half way up the block – in a place where I remembered a Chinese food takeout being – was a sign for Bickford’s coffee shop.

It had not faded – perhaps due to the sign over it all over these years.

No one seemed to take notice of it, except to glance up in angry over our stopping before it to stare. Certainly nobody but us saw this as anything of value, let alone a holy place where a handful of odd characters had gathered long go to plot out what would become the most significant social revolution of the 20th Century.

Liza, in a letter to Allen Ginsberg would recall her time spent here.

“Remember how we went to a year of movies on 42nd Street, seeing successions of nothing pictures about nobody people while we waited for our friend to finish work,” she wrote, “or sat in Bickford’s forcing patterns on the table top, our fingers pushing through the spilled sugar, our feet scraping on the tiled floor. We listened to the parade of pushers and passers who stopped at our table or sat there with us, drinking hot water and ketsup?”

Bickford’s had become a mythological place in the minds of those who admired the Beat Generation, but until that moment in the late 1990s, when Disney uncovered it in the way an archilogist might the sacred crypt of some ancient Egypt, most of our generation had never seen it – and typical of the lack of culture Disney had represented from nearly its conception – Bickford’s vanished again, defaced and demolished by the ruthless hands of construction workers, who could not have known its significance nor have cared if they had.

But there was irony in all this.

Disney and the Beat had evolved out of the same need to alter common place reality. Reportedly, Walk Disney had partaken of an early version of LSD, while the Beats had taken slightly, but equally mind altering paths through the Doors of Perception.

And yet, all these years later, the two entities came to represent quite opposite ideologies in the world.

In one of her columns, Liza once wrote about how people with long hair were not allowed in Disneyland in California in the 1960 – something I knew for fact since I had paid several visits to that world of imagination, once straight out of the Army when my hair was still short, and later when my hair was long. The first time I had no trouble getting in, but management tried to stop me the second time and relented only when I raised a ruckus. Fortunately, the delay was not too long since I had dropped several tabs of LSD prior to arriving, and managed to see Disney’s creation the way he had first imagined it when he had tripped so long ago.

Disney’s destruction of Bickford’s and the scrubbing up of Times Square seemed oddly appropriate, a symbolic gesture by a society desperate to forget the darker side of human experience, something Times Square seemed to represent and the Beats – including Liza ached to explore.

It was this sense of reality in Times Square that drew us all there – the Beats during the war years, and later my friend, Frank and I , as hippies.

Liza felt it, too, even before she met the Beats, recalling how she went there with her father to an oyster bar, and how her hormones throbbed over the sight of the sailors in the streets. She was about 14 and remembered how she ached, and how all the girls she knew wore sailors hats with the names of those sailors written on the inside.

While the Beats in those days came downtown from their haunts near Columbia University to explore that dark world and its edgy patrons, most of New York was edgier then, full of dark shadows and stark people, something Liza would recall later when she wandered along Skid Row in Los Angeles, seeing the tattoo parlors and the pawnshops, and the lost people stumbling from place to place without purpose. I saw it, too, when I got off the bus at the Los Angeles Bus Terminal in 1969 and wondered how after traveling 3,000 miles from New York I had come to a place that looked exactly like the place I had just left.

For Liza as a young girl, she didn’t have to go far to find the seamier part of life. She didn’t even have to leave her family’s apartment in Greenwich Village, but merely to look down at the street from the 5 th floor of her West 15 th Street apartment building to see the hordes of longshoremen, merchant sailors and neighborhood street gangs on the hunt for women.

“Remember, Carl?” she wrote later, “how I learned your songs on little cat’s feet, sung to me by mother mother’s pitch-less voice, city evenings on the 5 th floor where birds never came for window crumbs, view scapes of cement and miles down to plunge – death for children hanging frightened onto rusted safety bar. Close the window, dear, for fierce is the night air and ignorant armies clash by night on the curbside.”

This was not yet the Village of Simon and Garfunkel, but rather a twin city to the Hoboken depicted in “On the Waterfront,” a world full of speakeasies and packes of men off the docks or ships looking for women to accommodate them or hot poker or games of dices where they could lose their hard-earned pay – a place where men far outnumbered women and had to settled for uptown prostitutes when they could not get the few easy girls of poor virtue who hung out at drug stores or foot carts, willing to entertain the boys for a decent meal.

The Italian and Irish kids, who grew up on these streets, learned to get tough, and take what they wanted when they could find it, often fighting each other if only out of the boredom of their existence.

But Liza would soon learn one important fact of life in this world which would soon get the name of the New Bohemia, artists, gays, and others who came to explore the dark side somehow passed through this world unscathed, immune to the most violent gangs, who someone saw these whackos from places like Paterson, New Jersey, as somehow special, even in need of protection, and so strange as it seemed, even as the Irish fought the Italians, artists like the Beats were allowed to pass – dangerous mostly too themselves as time would soon show.